Join 8,000 Iceland Travel Fans & Unlock Exclusive Discounts

Subscribe and instantly receive free discount codes for tours, car rentals, camper vans, and outdoor gear — carefully hand-picked to help you save on your Iceland adventure.

- ✔ Instant access to exclusive discount codes

- ✔ Savings on tours, car and camper rentals

- ✔ Tips and inspiration for planning your Iceland trip

We here at Stuck in Iceland welcome guest bloggers who share our love of traveling around Iceland. Nick Miners is a renowned British photographer who likes to be Stuck in Iceland. A few years ago he visited the Westfjords and his visit yielded a lot of photographs that capture the very essence of our Island. He graciously shares with us in this blog post. We are grateful for his tribute to our country.

The prints of the photographs are available on his web site.

The Westfjords and Iceland are a cure for migraines

I don’t get migraines very often. In fact as far as I can remember, I’ve only ever had one. However if there’s a time and place to be when the bliss that comes with waking up with the migraine miraculously, wonderfully absent, it would have to be in the Icelandic countryside, in the 3am daylight of midsummer.

Book a hotel and a flight to Iceland

The relentlessly bright Iceland summer night

I will never forget the moment I woke that morning in May of 2009, having spent much of the previous afternoon and evening in the foetal position, buried under a duvet, trying to shut out the relentless daylight and birdsong from outside the window of our cottage in Hvalfjörður (Whale Fjord), 30km outside the capital, Reykjavík. The stress of trying to find our pre-booked car park at Gatwick airport that morning, while still allowing enough time to check-in to our flights, had finally got the better of me, and my body was protesting.

But as I gradually regained consciousness, the plaintive call of a curlew and the otherworldly whooping of a snipe became forever associated with the sheer blessed relief I felt, and it is now just one among many memorable moments I have spent in Iceland.

Going to the Westfjords

It was my fifth visit to Iceland, and the fourth I had spent with my small family, consisting of my partner, Caroline, our then 11-year-old son Joe and me. We had hired a small four-wheel-drive vehicle and were on a tour of the westfjords of Iceland, a region that had long fascinated me and one which I had been determined to explore at the earliest opportunity. Our first night was in the aforementioned cottage on the banks of Hvalfjörður.

Hvalfjörður is the first fjord you come across if you drive north from Reykjavík on route number 1, the Þjóðvegur (national road) which circumnavigates this Atlantic island, linking together the majority of the towns and villages which surround the uninhabitable interior. A tunnel, built in 1998, cut the journey north to the next nearest large town of Akranes by 45km, making the ferry which previously linked it with Reykjavík, via Faxaflói bay, redundant. However it is always worth making the detour as the fjord is a minor treasure, and if you have the time, you can hike from the far end of the fjord to Iceland’s highest waterfall, Glymur.

Clouds over Langjökull glacier

The view to the east on the morning after the migraine before was of variously layered clouds that had formed over the glacier Langjökull. Despite the long days, the northerly latitude of Iceland means that at this time of year the sun remains relatively low in the sky throughout the daylight hours. I had no hesitation in making up for lost photography time that morning before we left. Having been challenged before we left to shoot exclusively in black and white, I didn’t want to disappoint.

Going past the entrance to the Centre of the Earth

Our next scheduled stop was at a small farm near Hólmavík, on the gateway to the Westfjords. The road north took us through the small but attractive town of Borgarnes, where if you wish you can take the road west to the Snæfellsnes peninsula. Perched on the tip of this headland is the mythical glacier Snæfellsjökull, said by Jules Verne in his novel ‘Journey to the Centre of the Earth’ to be the gateway to the underworld. However as we had planned to visit the peninsula on our return journey, we continued on the Þjóðvegur, north to Hrutafjörður, where the road to the Westfjords splits off from the main ring road.

Snowball fight!

On the high ground north of Borgarnes we saw the first signs of snow that still linger in Iceland even this late in the year. The temptation was too great, so we stopped the car, and went for a snowball fight. No matter what time of year, there is something about snow that turns even the most earnest Brit into a six year old child again.

At Hrutafjörður we came across the tiny settlement of Prestbakki, where a church, which happened to feature on the cover of our guidebook, stood. Further north, still on the banks of the fjord, we came across a small group of beautiful Icelandic horses, a breed famous for its hardiness and good looks. These particular horses appeared to believe their own hype, and despite being unwilling to socialise with Caroline, appeared less reluctant to approach me and pose for photographs. The snowy tips of the mountains on the opposite side of the fjord provided a dramatic backdrop.

Oystercatchers and terns put on a show

Bitrufjörður and Kollafjörður, fjords which had not been bypassed by tunnels, made the journey to our next overnight stop a little longer than it appeared, but we eventually arrived at the small farm of Kirjuból, which overlooks the sea across Steingrimsfjörður, the wide Húnaflói bay and, beyond that, the open Arctic Ocean. Piles of driftwood, carried from who-knows-where to these northern waters, littered the coastline. And as had been the case all the while we had been on the road, the sounds of curlew, snipe, oyster catcher and arctic terns pierced the bitter sub-arctic air. I was able to practice a little of my rudimentary Icelandic with our hostess, who showed us to a well-equipped basement flat in her farmhouse. We wandered across the road to take in the crisp air and watch the oyster catchers and terns darting across the water.

We headed to Hólmavík itself that evening, to get something to eat, before resting our migraine-free heads for the night. As the crow flies, our next stop was only 86 km away, but the fjords that lay in our way made the journey by road a much more impressive 220 km.

Finally entering the Westfjords proper

The westfjords begin on the far side of Steingrimsfjarðarheiði. A mouthful, I know, but it can be broken down into manageable chunks: ‘Steingrims’ comes from Steingrimur the troll, a viking who is said to be buried in the hills overlooking the fjord; ‘fjarðar’ is a form of the Icelandic word fjörður meaning fjord; and heiði (the name for the high ground between valleys, equivalent to the English word ‘heath’). So, the heathland of Steingrimur’s fjord – a pretty typical descriptive name of the kind given to most Iceland places and geographical features.

My most memorable photograph of Iceland

At the highest point in Steingrimsfjarðarheiði is a much photographed (though I didn’t know it at the time) stone shelter. Shelters of this kind can be found throughout Iceland and are stocked with food, blankets and fuel. This one was surrounded by a blanket of featureless snow, several feet deep, and I was able to capture what to me has become my most memorable image of Iceland.

Descending to sea level again, we came across the fjord called Ísafjörður. Confusingly, this is not the fjord on which the town of Ísafjörður, which was our destination, sits, but is instead a 16km long fjord flanked by shingle beaches and 200-300m, high mountains. At the southern tip of the fjord we stopped to admire the view back towards its mouth.

Spotting a sea-eagle

The rest of the drive that day consisted of travelling up and down fjords, with the exception of Mjóifjörður which has a low bridge across its mouth. At one point we thought we spotted a sea-eagle (also known as a white-tailed eagle) flying over the water at Hestfjörður. and an animal skull lay discarded at what looked like an abandoned agricultural settlement. Milky water foamed down a cascade at Skötufjörður, and as we drove on the headlands between fjords, the snowy peaks on the remote, roadless peninsula on the opposite side of the main Ísafjarðardjúp fjord, which feeds all the smaller fjords we were travelling along, touched the low cloud. Beyond them, unseen from where we were driving, lay the nature reserve of Hornstrandir, Iceland’s most remote coastal region, where there are no roads, only hiking trails; and the arctic fox sits unchallenged at the top of the food chain (except when the occasional ice-bound polar bear drifts ashore).

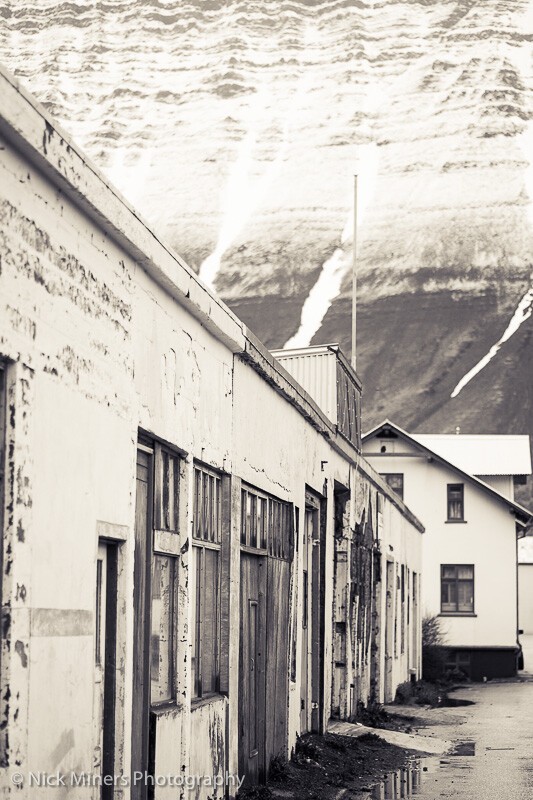

The oasis of civilisation

The town of Ísafjörður is the capital of the Westfjords region, and is an oasis of civilisation in this isolated region. The population of roughly 2,500 people live on a spit that juts out into Skutulsfjörður. We were booked into the main hotel for two nights, and our room had a very special view over the fjord, looking south towards the twin peaks of Háafell and Hnifafjall, which straddle the river Ulfsá. As midnight approached, the waters of the fjord became very still, yet the daylight never faded, and the mountains were reflected in the mirror-like surface.

The Westfords tunnels

The road from Ísafjörður to the rest of the Westfjords used to head over land through Breiðadalsheiði. This road was vulnerable to extreme snow cover, something which happens often this far north, so for many years access to the rest of the towns and villages south of Ísafjörður was by boat only, except in the very best weather.

To rectify this, the Icelanders built a tunnel linking Ísafjörður with Súgandafjörður and Önundafjörður, the northernmost fjords on the Atlantic-facing side of the region. Opened in 1996, the Vestfjarðargöng (Westfjords tunnel) is an impressive three-pronged structure, with the subterranean t-junction half way through one of the weirdest things I have seen.

We turned right at the t-junction on the first day after arriving in Ísafjörður and drove to the town of Suðureyri on the southern bank of Súgandarjörður. The fjord is one of the narrowest in Iceland, and is bounded on the north by Ásfjall, a table mountain about 300m high, cut through with valleys carved over the millennia by the streams that feed the fjord.

The sleepy town was basically a cluster of houses and a church gathered round a small harbour, with strips of fish drying in cages to deter the greedy local seabirds. We watched fulmar, similar in appearance yet unrelated to the gulls common back home in the UK, fly silently in loops around the harbour, staying close to the water in the hope of finding food. When you’re used to the din made by gulls, the silent fulmar seem almost zen-like by comparison.

Site of a tragic avanalanche

We travelled back through the tunnel and drove along the north bank of Önundarfjörður to the town of Flateyri. This larger (by Westfjords standards) town was the site of a disaster in October 1995 when an avalanche struck, killing 20 of the 300 or so inhabitants. To prevent such a tragedy happening again in the future, banks were built up on the slopes of the mountains behind the town to divert snow away from the populated centre of the town.

Tasty cardboard!

The approach to the town took us past another set of fish-drying frames, where more harðfiskur was being prepared by nature. Harðfiskur is a very light, nutritious food, and is one example of the type of Icelandic food that packs goodness into small packages, and was favoured by the Vikings who spent months at a time at sea. To taste it takes patience – at first it feels like you are eating cardboard, but after some determined chewing the flavour of the fish is released, making for a very pleasant snack. The racks here were covered with hundreds if not thousands of individual animals, the sort of sight you only ever see in Iceland.

On the opposite side of the fjord, it was possible to get a view of the town and the avalanche protection looking over it. I set the camera up for a panoramic view of the whole fjord, using a combination of 7 images.

Going to see the waterfalls

The next day was the one I had been looking forward to most. We had reserved accommodation in a guest house at the southern end of the Westfjords, on the banks of Patreksfjörður. The guest house was called Hótel Látrabjarg and was named after the nearby bird cliff, which is the home to Europe’s largest colony of puffins, razorbills and guillemots. The cliff stretches for 14km from the most westerly point in Iceland (and, indeed, all of Europe) and reaches heights of 440m. But more on that in a moment.

The route south from Ísafjörður was, like the route from Hólmavík, made far longer by the intervening fjords. A straight-line distance of 70km took us along 210km of roads, but the extra mileage was worth it.

The giant Dynjandi Waterfall

Iceland is famous for many things, but chief among them are its waterfalls. I’ve already mentioned Glymur in Hvalfjörður, but the waterfall which has the distinction of being Iceland’s loudest is called, appropriately enough, Dynjandi (which is Icelandic for ‘thundering’). It is part of a series of waterfalls that flows into Arnarfjörður, the Eagle Fjord. As the water cascades down the steep mountainside it spreads out into an upside-down fan shape, and when we first caught sight of it from across the other side of the fjord, we stopped the car and opened the window and could clearly hear the rushing water from our vantage point over 10km away.

From close-up, the waterfall is even more impressive, as it is hard to get an idea of its scale unless you are standing right beside it. If you look closely at the photo below, you may be able to spot Caroline and Joe standing at the base of the cascade.

The drive over the higher ground along the eastern edge of Arnafjörður took us through some more snow, so of course we stopped once again for a snowball fight, before reaching a headland with a spectacular view back over the fjord.

Visiting the puffin colony of Látrabjarg

After a delicious home-cooked meal of fiskibollur (traditional Icelandic fish balls) and blueberry skýr (a type of yoghurt) once we arrived at the guesthouse, we headed out again to Látrabjarg. Being so far north meant that even though it was approaching 10pm by the time we reached the cliffs, the sun was still well above the horizon, and the puffins (something else for which Iceland is famous) were all back from hunting at sea. The noise—not to mention the stench—was all-encompassing.

The iconic puffins

Puffins are a lot smaller in real life than you expect, and they are also extremely tame birds. They nest in burrows which they dig with their huge, sharp beaks, and as such are generally unthreatened by predators, meaning the presence of humans bothers them no more than the presence of the other birds that share the cliffs with them. The razorbills tend to keep to lower levels, living on the vertiginous precipices further down the cliffs, but we did spot one individual stubbornly guarding its nest at the top among the puffins. Across the water, over 80km away, the aforementioned Snæfellsjökull glacier, gateway to the underworld, was shining like a beacon from its perch at the tip of Snæfellsnes.

Catching the midnight sun

After watching these amazing birds for about an hour we headed back to Patreksfjörður to catch the famous midnight sun. A little further along the fjord from our accommodation was a lighthouse, which made a striking silhouette against the sea. On the very stroke of midnight, the sun was just brushing the horizon, but our busy day had been all too much for Joe, who had fallen asleep in the back of the car.

Last day in the Westfjords

Our next day was our last in the Westfjords; a drive up and down the fjords on the southern end of the roughly triangular-shaped peninsula was followed by a long haul to a small farm that awaited us in Haukadalur valley. On the way we didn’t have time to stop much, but we did spot Vaðalfjöll, an unusual mountain with a double-peak that loomed over much of the road as we left the Westfjords region.

Photographing the rugged coast of Snæfellsnes peninsula

We had planned the next day to tour the Snæfellsnes peninsula. Unfortunately the ice cap was hidden under cloud that day, but the Atlantic Ocean was churning nicely, so we parked the car at the very tip of the peninsula at Öndverðarnes where the waves crashed ceaselessly against the volcanic rock, spraying seawater and seaweed everywhere. It’s the sort of natural spectacle that you can watch forever—despite the monotony, it’s a soothing, relaxing experience.

Dramatic Ólafsvík

Heading back along the northern edge of the peninsula the rain and sun combined in equal measure to make the small town of Ólafsvík appear overly dramatic. Further along the road, a break in the clouds resulted in a spot of sunlight passing across one side of Kirkjufell (Church Mountain), a much-photographed feature of this part of Iceland.

A rainbow in all of its splendour

We spent the last night and day in Reykjavík itself, a bit of a shock to the system after the isolation of the previous week. Relative calm was found on the Seltjarnarnes peninsula, the tip of the headland on which Reykjavík sits, where a rainbow appeared over the bay. As much as I enjoyed trying black and white photography, it doesn’t really do justice to the phenomenon, so I will have to end on a colour photograph.

Thanks to Hjörtur Smárason for the additional historical information.

Photographs and words by Nick Miners.

© Nick Miners Photography