Free and exclusive discount codes for hundreds of tours and & travel services in Iceland

Subscribe to instantly receive discount codes for tours, car rental, camper van rental, and outdoor clothing rental. Thank you! ❤️ Jon Heidar, Editor of Stuck in Iceland Travel MagazineFor the longest time, the history of Iceland has been told this way: Noble Norwegian chieftains wanted to be free of the aggressive king Haraldur Hardrada, who unified Norway with force. These intrepid chieftains wanted to live free in remote Iceland rather than bend the knee to a power-hungry king. The start of the settlement is dated neatly to 874. This is when the first settler, Ingólfur Arnarson, is said to arrive in Reykjavik. However, as archeology evolves, the Icelandic origin story becomes more nuanced than the original Icelandic sagas and the Book of Settlement indicate. The most dramatic example of how the history of Iceland is being rewritten is the Caves of Hella. Scientists have now started studying their origins.

Over two hundred human-made caves in the South of Iceland

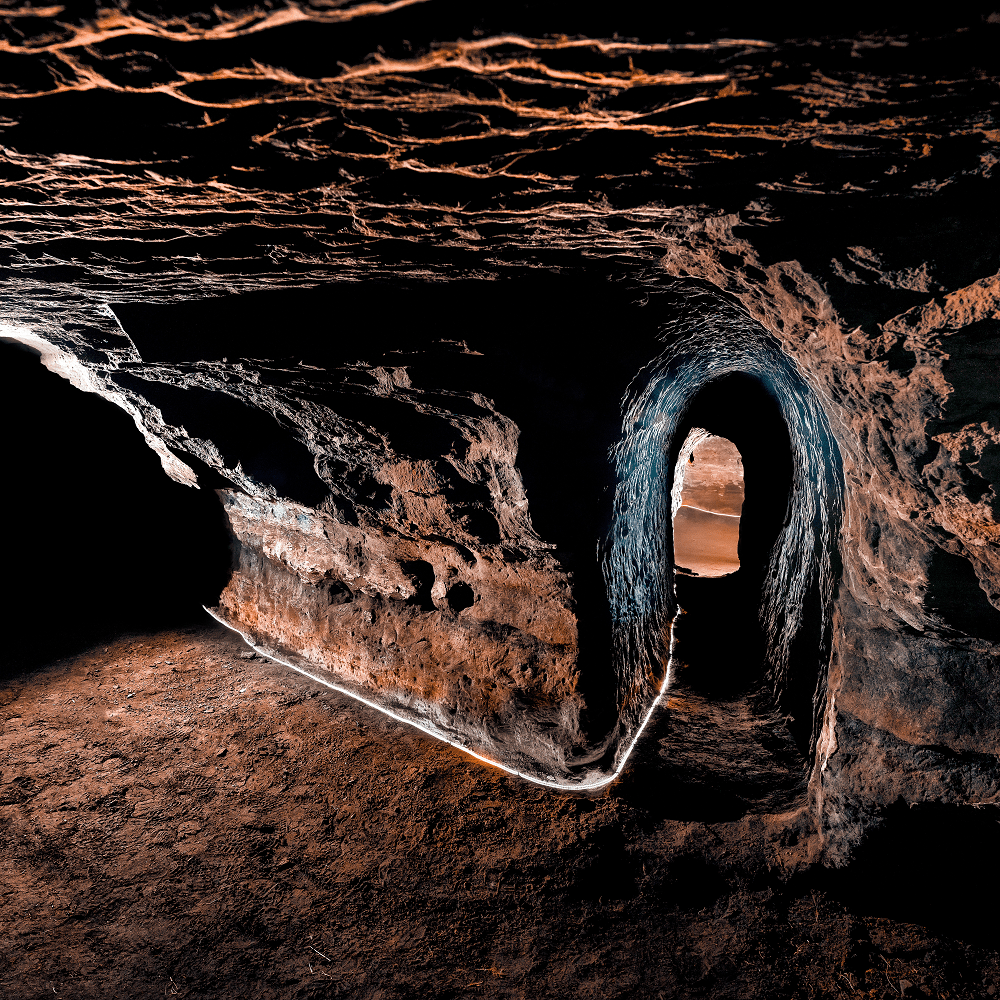

Consider the excavation at the Viking age site at Stöðvarfjörður in the east of Iceland, which reveals human activity before 874. In the Settlement Museum in Reykjavik, one displays the remains of a turf wall erected before 874. At Hellnar, there are big human-made caves with uncertain origins. There are two hundred known man-made caves between Hveragerði and Vík in the South of Iceland. The caves are carved into the tuff, common in the region, and their age and origins are unknown. It is tempting to associate them with Irish hermit monks who are said to have settled in Iceland to worship their God in peace. They were known to the Norse people as ‘papar.’

Caves of Hella are in a league of their own

The caves of Hella on the farm Ægissíða in the village of Hella are in a league of their own. These huge caves are considered the oldest still-standing archeological remains in Iceland but their age and origins are a mystery. Many want to connect the caves of Hella to Celtic people rather than Norse settlers. The sagas mostly describe Celtic people as thralls, or slaves, to the Norse ruling class. The real story may be more complicated.

Meeting Jesus underground

Meet the professor who is now the custodian of the Caves of Hella

I have visited the caves, and they are impressive. Two years ago, I spent an evening in one of the caves listening to a local storyteller stating his case that the Icelandic Saga of Burnt Njál was, in fact, really about a clash between Norse and Celtic settlers. He was sure that the cavernous space we were in was an ancient church carved by Celtic settlers. I sat in the gloom underneath alcoves in the rock wall, which would be perfect for candles, looking up at the speaker, who looked like a priest preaching to his flock before an altar, and thought it was plausible. After all, at the back of the church, there is indeed a cross with a hint of Jesus carved onto it.

The same family has occupied the farm where the caves are for about two centuries. Its most well-known member is Baldur Þórhallsson. He is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Iceland and is the Research Director of the Centre for Small State Studies. Indeed, Baldur is often on Icelandic media, where he casts a light on both domestic and international affairs. His family runs the tour company The Caves of Hella, and since 2019, it has offered visitors a chance to step into the caves and back into the mysterious past.

Hello, Baldur, and thank you for taking the time for this interview. When did you first become interested in the caves of South Iceland?

A special passion for undiscovered treasures developed with my grandfather’s storytelling of Papar, Irish monks, whom he steadfastly believed settled and lived, according to oral history, in the twelve man-made caves on our farm, Ægissiða, by Hella before the Nordic settlement in Iceland. My grandfather and parents still used half of the caves in the 1970s and 1980s. They were used for hay and as a storage for food, such as potatoes, homemade jam, and extracts.

The caves were a big tourist attraction when they were open to the public. We had thousands of visitors every year, Icelanders and foreigners, fascinated by the origin of this underworld of the south. I was only five or six years old when I started showing the caves to tourists when my grandfather was busy working on the farm. I simply tried to remember every word my grandfather told visitors and tried my best to make myself understood even though I spoke Icelandic to the foreign visitors.

What are your theories about the origins of these man-made caves? Who made them and why?

Mystery surrounds the phenomenon of the caves, and for centuries, people have wondered who made the caves. We believe our ancestors when they say that Celts made the caves before the settlement of the Vikings in Iceland. The Celts, Papars, were Christian, and there are indications that Christian people lived in the caves or at least used the caves. For instance, one of the caves bears the name the Church (Kirkjuhellir), and there are fascinating Christian crosses in another, Fjóshellir.

What happened to the Celts?

We don’t know what happened to the Celts. They may simply have mixed with the Nordic men. The latest genetic evidence indicates at least that my grandfather was right about Icelanders’ Celtic roots. We are still digging (also in concrete terms) for evidence about the settlement of Papar in our land. The Icelandic historical narrative claims that we are all the offspring of the brave and glorious Vikings. It does not give any scope for other interpretations, such as that our ancestors were Christian Celts. This is a story that could not be told. We are opening this Pandora box.

Can you describe the work involved in restoring the caves?

The caves were abandoned after farmers stopped using them in the 1980s. We restored the caves by rebuilding their large entrances, which are made of turf and stones. Their chimneys/vents, made of stones, also needed restoration. The caves must also be cleaned out since they quickly get filled with sand and dirt if not closed. We made them accessible to visitors by lighting them, placing a glass ceiling on the chimneys, and making trails between them. Four caves are now open to the public, including two of the largest caves. They can host around 150 people each.

Apart from the caves of South Iceland, what are your favorite places in Iceland?

My favorite place in Iceland is Landmannalaugar, a place in the Fjallabak Nature Reserve in the Highlands of Iceland. It is a stunning place. I like to hike in the area and dip into the natural geothermal hot springs. My favorite walking route is Fimmvörðuháls between Skógar and Thórsmörk. The view from the trail is incredible.

If my readers are interested in visiting the man-made caves of Hella you have helped restore, what should they do?

We offer daily guided tours in the caves. Our guests experience the wonders of the caves, including ancient crosses, wall carvings, and carved seats, and tell them, of course, our story. We visit four caves, and the entire tour takes about one hour. We also offer a private luxury cave experience. They have also become very popular. Included in our luxury tour is private guidance, whisky and beer sampling, and delicacies, all made locally. And a local luxury hotel, Hótel Rangá, offers a Viking feast in one of the caves. Guests enjoy gourmet food and explore the caves.

Moreover, the caves have become for weddings and concerts. They provide amazing surroundings for special events, such as weddings. Please contact info@cavesofhella.is if you want to visit the caves or attend the private tours. You can also find information about us on our website and on Facebook, and get in touch there.

What advice would you give to people visiting Iceland for the first time?

Continue to be adventurous. Enjoy the rainy days and the strong wind. Walk in nature, climb a hill, and dig into the underworld.